The first thing you notice about Brittany is a sense of age – most villages have 300+ year old houses, 500+ year old churches and maybe a 5000 year old standing stone. Over the last 3000 years, nine different groups have left their mark on its landscape, architecture and social history. The result is a unique language, cuisine and culture that is as Celtic as French. Through this rich and historic landscape, touring routes have been constructed gentle enough for family groups, yet with plenty of interest for the seasoned tourer and easily accessible by ferry from the UK.

The tour uses three French national cycling routes

- The Vélodyssée is France’s longest waymarked cycle ride, a 1200 km long cycle route along the Atlantic coast, forming the French part of EuroVelo 1. It crosses Brittany from the Channel at Roscoff to the south side of the Loire estuary at St-Brevin via Redon before following along the Atlantic coast to finish at Hendaye on the Spanish border.

- Route 42, links Saint-Malo to Redon, via the Canal d’Ille et Rance and the Villaine valley before connecting across to the coast at Arzal

- The Velocéan will eventually connect Roscoff via Arzal to the north side of the Loire Estuary at Saint-Nazaire, from where, St-Brevin is a short bus connection away over the Saint-Nazaire bridge. Currently it is signposted from Caire.

Joining these together, a figure-of-eight route can be constructed, based out of the channel ferry ports, with a crossover at Redon. This connects most of the main sights of central Brittany and provides an excellent base for exploring its history, culture and cuisine in a fortnight’s, mostly traffic-free, tour of this beautiful duchy.

Resources

Tour Duration: 14 Days

Undertaken: June-July 2022

Story Map: A multimedia site using photographs, videos and maps to tell the story of the tour

Outdoor Active Collection: Link to descriptions and gpx files for each of the 14 days in the tour

eBook: 150-page travelogue can be purchased describing the sights, sounds and food to be found on the route together with maps at 1:120,000 scale

The Route

The 14 days of cycling have been broken down into seven, 2-day sections, each with their own theme. More details on the sights and experiences to be found during each can be found in the Story Map link above. GPX route files for each day can be downloaded from the Outdoor Active collection above.

| Day | Start | Finish | Length | Ascent | Time |

| 1 | Roscoff | Morlaix | 30km | 350m | 2h00 |

| 2 | Morlaix | Carhaix | 66km | 660m | 5h00 |

| 3 | Carhaix | Pontivy | 86km | 420m | 6h15 |

| 4 | Pontivy | Josselin | 54km | 110m | 4h00 |

| 5 | Josselin | Redon | 74km | 330m | 4h45 |

| 6 | Redon | Camoel | 56km | 380m | 4h00 |

| 7 | Camoel | Batz-sur-Mer | 76km | 290m | 4h00 |

| 8 | Batz-sur-Mer | Saint-Nazaire | 55km | 160m | 3h30 |

| 9 | St-Brevin-les-Pins | Nantes | 65km | 180m | 4h30 |

| 10 | Nantes | Blain | 59km | 170m | 4h30 |

| 11 | Blain | Redon | 46km | 50m | 4h00 |

| 12 | Redon | Rennes | 89km | 140m | 6h30 |

| 13 | Rennes | Dinan | 79km | 180m | 6h00 |

| 14 | Dinan | Saint-Malo | 30km | 130m | 2h15 |

Route Description

Traded Wealth: Roscoff – Morlaix – Carhaix

Effective roads only reached the north coast of Brittany during the 20th century, so the area has always been dominated by its relationship with the sea. Even before Julius Caesar conquered the area in 57BC, the local Gallic tribe, the Osismii, had developed Europe-wide trade in bronze from the tin deposits on the peninsula. Caesar took over their capital (modern-day Carhaix) as Rome’s regional centre Vorgium, from where the Breton coastline was administered.

After the collapse of the Roman empire, seaborne waves of immigrants from Devon, Cornwall and Wales populated the region, amongst them Paul Aurelian, a 6th century Welshman, who established monasteries and became one of the seven founding saints of Brittany (Saint-Pol).

With maritime trade far easier than by land, and a fertile soil, considerable fortunes were made by seafarers and traders, especially in linen, resulting in magnificent houses in Roscoff and Morlaix, and ornate village calvaries such as that in Plougonven.

The Monts d’Arrée were a constant barrier to trade, so local towns built their own rail network to cut through the forests, opening up access to towns like Huelgoat, with its rocky tors and Arthurian legends, before reaching Carhaix.

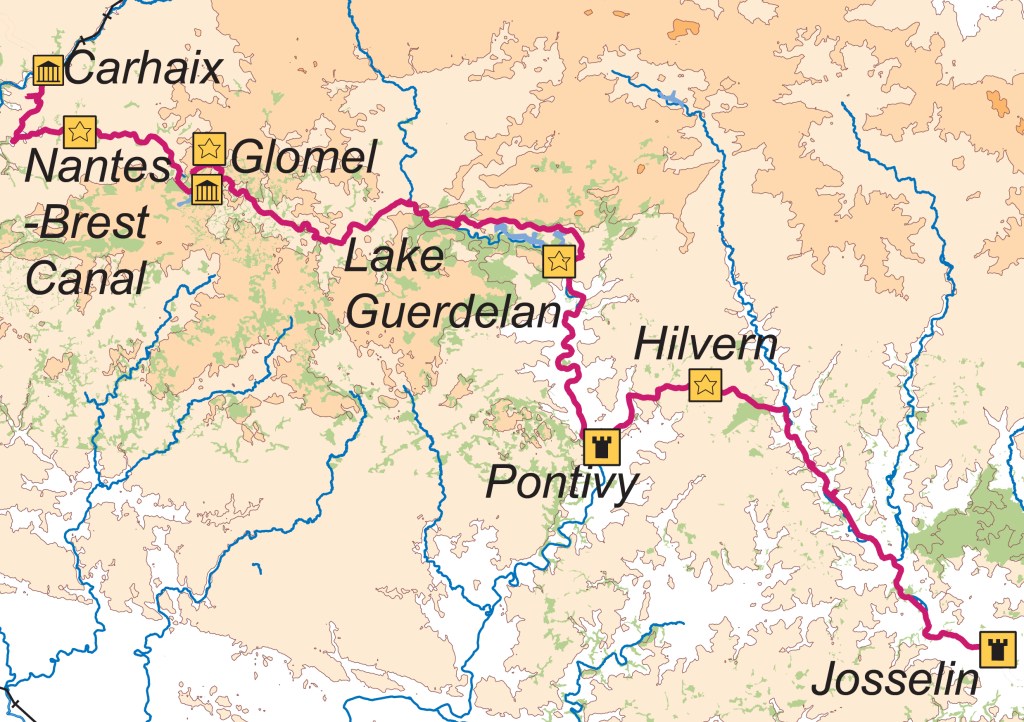

Engineered Countryside: Carhaix – Pontivy – Josselin

For the next couple of days, I would be following the towpath of the Nantes-Brest Canal. Originally one of the remoter parts of Brittany, the countryside has been engineered over many thousands of years to its form today. The threat of war has been the major driver; the monumental castles at Pontivy and Josselin are the legacy of the 14th century Breton War of Succession, and the canal itself an 18th century by-product of Napoleon’s war with Britain.

When coupled with the erection of the huge Neolithic dolmen at Glomel, and the 20th century Lake Guerlédan with its dam and hydro-electric power station, the terrain is very different from that which nature designed.

Geological Meanders: Josselin – Redon – Arzal

The geology of Britany, known as the Armorican Massif, consists of the bases of ancient volcanoes which erupted 300-600 million years ago. They once would have been as high as the Himalayas, but now form a plateau no more than 400m high, distinct from the younger rocks found to the north and east in France.

The granites and gneisses of those eroded bases have subsequently been compressed and faulted to leave long hard ridges interspersed with valleys of softer rock in a broadly south-east to north-west orientation.

The rivers however flow roughly north to south from the highlands of the plateau to reach the Villaine at Redon, which then flows westward to the Atlantic. Inevitably the ridges and rivers meet, with the latter first diverted to flow alongside the former, but eventually such as north of Redon, they find a weakness and cut through, forming a gorge and resuming their direction of flow. Settlements evolved at strategic locations within this landscape, some at river crossings and junctions such as at Malestroit and Redon, some on the heights controlling the rivers such as La Roche Bernard, and some on the ridges above for protection like at Rochfort-en-Terre.

Salted Living: Arzal – Batz-sur-Mer – Saint-Nazaire

The Atlantic coast of the Guérande Peninsula, set between the Villaine and Loire rivers is very different from the northern coast facing the English Channel. Water is the principal source of both transport and nutrition, with much of the land covered in wetlands unsuitable for cultivation. As a result, communities have developed facing the sea.

Even in pre-Roman times, the local tribes, the Veneti and the Namnetes, were skilled mariners, with strong trading links to Britain. Indeed, so well-built were the Veneti boats that the Romans struggled to match them on the ocean and had to evolve new tactics to eventually subdue them. Salt became the cash crop from the Middle Ages, with Guérande salt exported all over Europe. Whilst this trade has declined, the mariculture of shellfish has taken over with many bays devoted to its production.

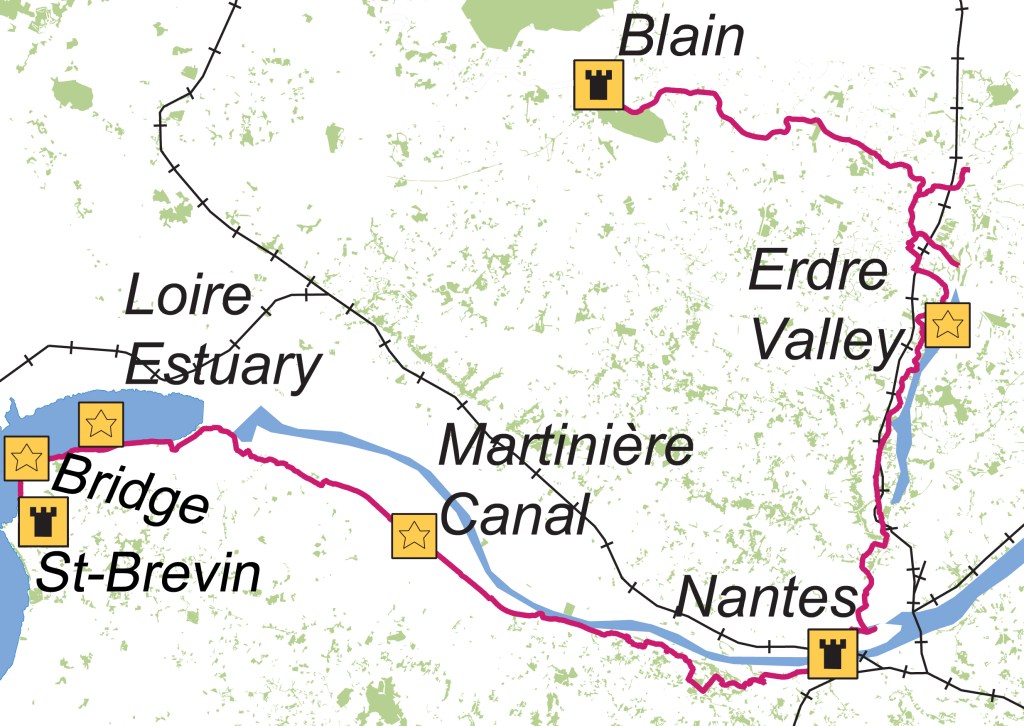

Dislocated Lands: Saint-Brevin – Nantes – Blain

Loire-Atlantique is one of the original 83 departments of France. Annexed by the Bretons with Viking assistance, it was part of the historical Duchy of Brittany, and contains Brittany’s medieval capital, Nantes. However, during World War II, the Vichy Government removed it from Brittany and added it instead to the Pays de la Loire – reconfirmed after the war.

The Loire is France’s longest river, rising in the Massif Central, some 625 miles away and is tidal from Nantes to the sea. It was a major route for trade until the rise of rail, starting with the Gauls who used it to transport metals from Brittany to the Rhone valley and by 1700, Nantes had more watercraft than anywhere else in France.

Until the Revolution, Nantes prospered on the Loire’s access to Atlantic trade in slaves and sugar, becoming France’s primary port. Eventually, however, the increasing draught of ships and shallowness of the estuary cut it off, until modern dredging techniques reopened the channel.

Nowadays, together with its tributary the Erdre, the river has a great role to play in the natural environment, providing large expanses of marshes and lakes, and supporting rich and varied wildlife.

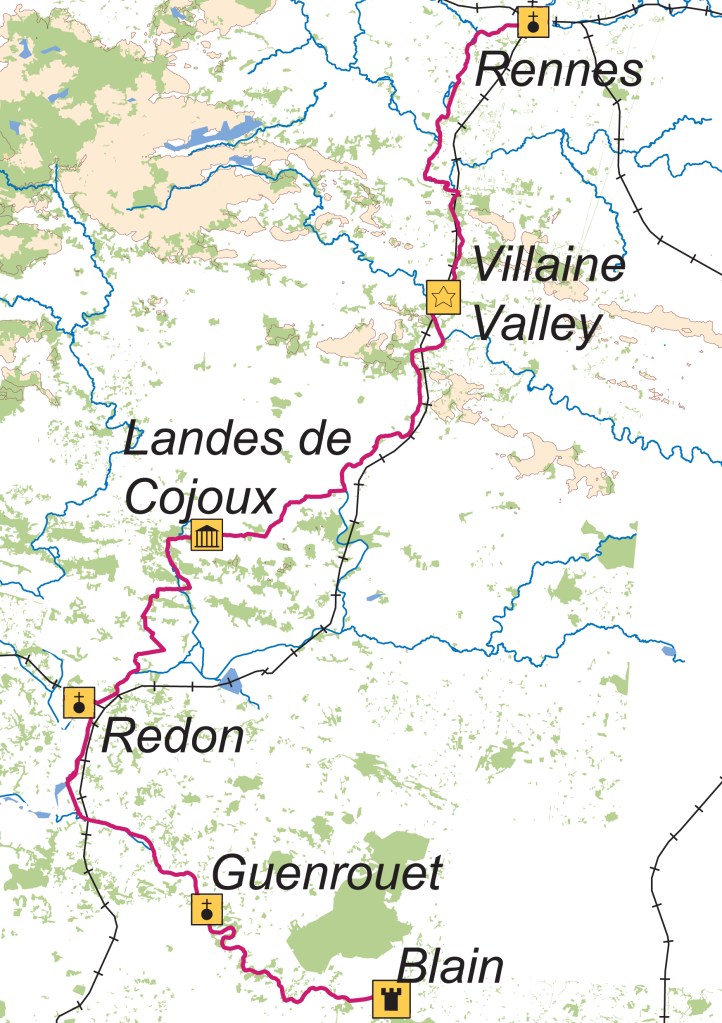

Pilgrims’ Progress: Blain – Redon – Rennes

A pilgrimage was one of the riskiest personal trials that a medieval person could undertake. Motivations included religious devotion, gaining an indulgence, expiation of sins or penance. They could take several years, and likely would involve facing bad weather, brigands and wild animals, making our modern-day cycling tours seem mundane.

Whilst the trail to the relics of St. James in Compostela has been popularised today within Spain as El Camino, someone attempting that from western Britain or Ireland in medieval times would have started in Brittany from abbeys on the coast. Pilgrims from St-Mattieu, Locquirec and Beauport would have met outside Redon and continued along the rivers to Nantes and those from Mont Saint-Michel and Saint-Malo would have travelled via Rennes and met them at Blain.

These ancient routes along the rivers Isac and Villaine are decorated with ecclesiastical history. This terrain however has been worshipped for much longer. In the Landes de Cojoux, near Saint-Just, can be found a sanctuary dating back 7,000 years which would have been of equal importance to Neolithic pilgrims, with megaliths aligned to the solstices.

Protected Spaces: Rennes – Dinan – Saint-Malo

As you get closer to the English Channel, then armies find it easier to move around and the need for town protection, as opposed to a castle for the local lord, increases, whether it be from Viking Raiders, English forces in the Hundred Years War, or indeed French forces during the Breton War of Succession, as was the case with Guerande.

As a result, many towns were fortified at the time, although most have since lost their walls. In Rennes, simply a single gate remains, however Dinan has retained its ramparts from the 13C, whilst those in Saint-Malo were built over hundreds of years between 12C and 18C.

Neither has been breached in 700 years as English Forces were repulsed at Dinan by Bertrand Du Guesclin in 1359 and English raiders took St-Servan rather than Saint-Malo when flushing out Malouin privateers in the 18C.

Logistics

Travel

Brittany Ferries travel from Plymouth to Roscoff and Saint-Malo to Portsmouth on a near daily service. At the time of my trip, these were overnight from the UK with the return during the day.

There are a number of SNCF Stations at points along the route, notably Morlaix, Redon, Saint-Nazaire, Nantes, and Rennes.

Accommodation

I used the French Accueil Velo scheme to find accommodation. Service providers need to be within 5km of a national route with secure bike parking and covers both hotels and campsites.

I hotels I used were generally in the range €60-€80/night except Nantes, Dinan, Saint-Malo which were more expensive. Cycle storage was mostly indoors (2 out of the 14 were outside), 1 was in a public space and hence less secure, and in Saint-Malo I had to pay to access the hotel car park.

Weather

The weather in late-June/early-July was pleasant for cycling – warm, not hot and mostly sunny. However there were days with occasional heavy showers as would be expected in the summer

Bikes

I used a standard steel-framed touring bike with 700x38c tyres. This was the best choice for the ride as about 80% is off-road on well-graded tracks, although there were times that it was stonier – Route 42 from Redon to Arzal, and sandier – Velodyssee crossing the Monts d’Arree.

Climbs were mostly gentle – the steepest ones were when I was heading off-cycleroute to hilltop towns such as Rochefort-en-Terre and Dinan. My bike has a 1×12 setup (11-50/38) which was more than sufficient.

Waymarking signposts were generally very good on the national routes, I only lost them twice in Morlaix and leaving the city of Nantes. GPX routes on my Garmin GPS were useful at that time and also when heading off-route to nearby sights such as Plouvongen and Huelgoat.

There were several bike repair stations along the canals which I found useful for topping up my tyres.

Food

As pretty much anywhere in France, there is plenty of high quality, moderately priced food. Most restaurants serve local wine by the carafe and local Breton cider in a cup.

Late-June/Early-July appeared to be out of the main season as I found it a challenge to find restaurants that were open. There was only one open in Redon on a Sunday, none in Camoel on a Monday and one again in Batz-sur-Mer on a Tuesday.

Both single restaurants were creperies – a Breton specialty. The savoury galettes are always worth trying – made of buckwheat, a gluten-free grain, they are filled with a variety of local produce – ham, mushrooms, eggs, cheese, tomatoes etc and a meal in themselves. Sweet crepes for pudding are more traditionally French.

Boulangeries for a filled baguette for lunch are not as widespread in villages as I had expected – I always stopped at the first one I saw.